(A Beginner's Guide to) Learning the Night Sky (3rd Ed)

is available through Central Texas Astronomical Society ANDStargazer's Life List

Stargazer's Life List is now out-of-print for hard copies but e-copies are available free via Dropbox. It is available in either PDF or Microsoft DOCX

format (but not Kindle format). The nature of this book is such that you might wish to use it as a "working" document - that is, you might wish to personalize

it by adding objects, recording your own observations and notes, etc. If so, you will want the DOCX format where it can be edited using Microsoft Word.

(Keep in mind, however, that adding text will add pages; and this will then alter the page numbers, making them different from those cited

in the Table of Contents and Index.) Dropbox is a service by which one can access and download files. You do NOT need to have a Dropbox account, and this service is free.

(Note: So that you can find the downloaded files, note into which folder on your computer the files are downloaded; you may be able to direct the files

into your folder of choice, or they may go into a general Download folder.)

Once downloaded on your computer, you may print all or selected parts of the book for your own use or simply use/read it electronically.

* Click here to download Stargazer's Life List (PDF format).

* Click here to download Stargazer's Life List (DOCX format).

PS: Should you have difficulties accessing or downloading these files, email me at paulderrickwaco@aol.com and I'll see if I can help you.

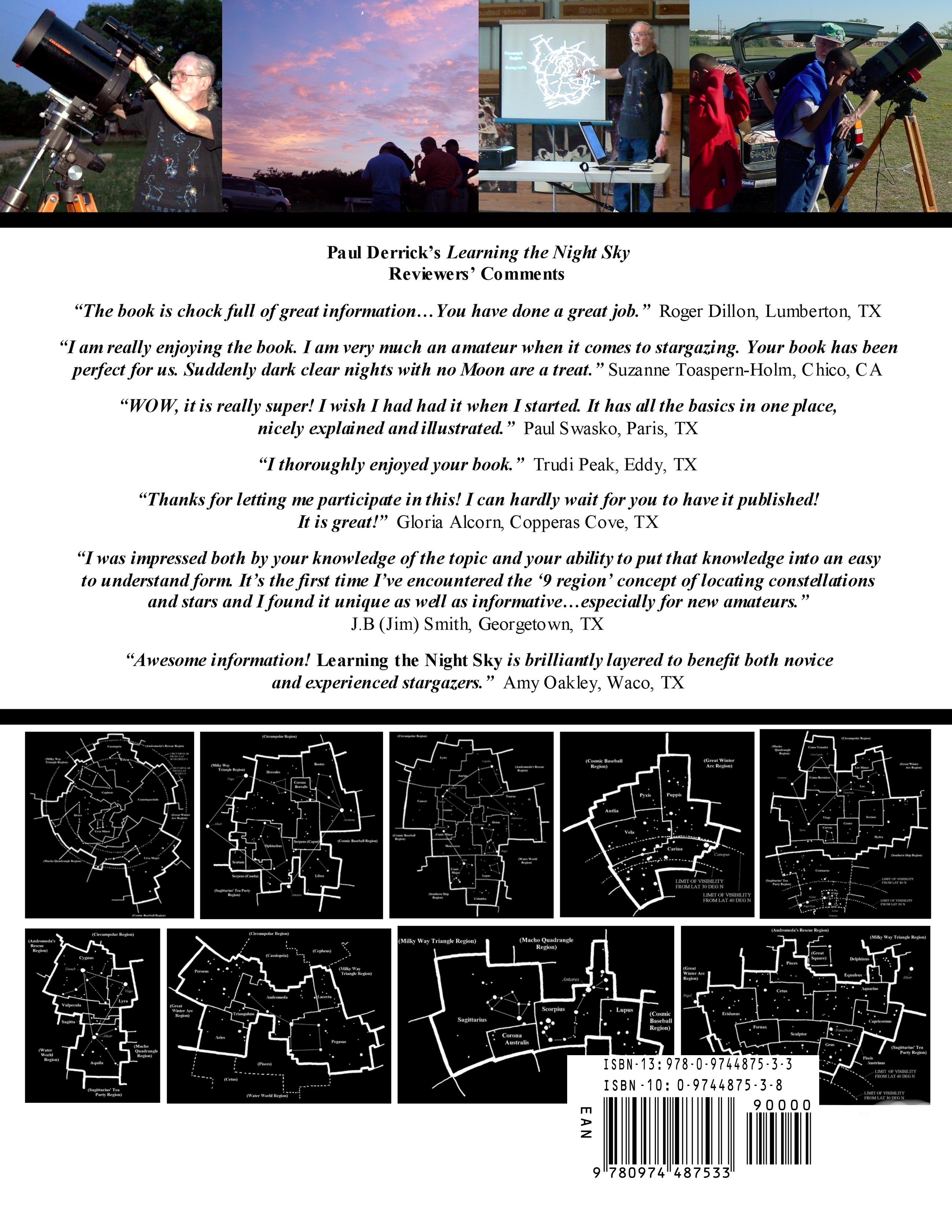

(A Beginner's Guide to) Learning the Night Sky (3rd Edition)

Published in 2008, 2015 / ISBN 0-9744875-3-8 |

|

(A Beginner's Guide to) Learning the Night Sky, 3rd Edition is a 206 page, 8½" x 11" soft-back, wire-bound book for novice stargazers and veterans. It contains over 150 photos and illustrations.

* The first section contains stargazing basics especially useful for new stargazers.

* The second section presents my approach for learning the night sky using nine sky regions, including the stories I tell during sky tours and classes and highlights of the region.

* The third section is a potpourri selection of 32 "best of" my Stargazer newspaper columns.

* The fourth section contains Stargazer's favorites, my selection of 263 favorite night sky objects.

* The fifth section contains handy reference information.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction

Part 1. Stargazing Basics

One's Personal Journey to the Stars

Getting Oriented

Movement in the Night Sky

Cosmic Distances

Objects for Observation: Solar System

Objects for Observation: Deep Space

Appearances

Angular Distances

Factors Affecting Stargazing

Time

Stargazing at Different Latitudes

Stargazing Equipment

Part 2. The Night Sky by Regions

Learning the Night Sky

Circumpolar Region

Great Winter Arc Region

Southern Ship Region

Cosmic Baseball Region

Macho Quadrangle Region

Sagittarius' Tea Party Region

Milky Way Triangle Region

Andromeda's Rescue Region

Water World Region

Part 3. "Stargazer Potpourri

People

Science

Explorations

Historical

Personal

Part 4. Staqrgazer's Favorites

Circumpolar

Great Winter Arc

Southern Ship

Cosmic Baseball

Macho Quadrangle

Sagittarius' Tea Party

Milky Way Triangle

Andromeda's Rescue

Water World

Deep Southern Hemisphere

Solar System

Brightest Objects

Part 5 Reference Information

The Greek Alphabet

The 88 Constellations

Constellations by Region

Bright Star Constellations, Ecliptic Constellations

Milky Way Constellations, 21 1st Magnitude Stars

Characteristics of Planets

Characteristic of Planets' Orbits

Handy Conversions, Calculations

Useful Geometry

Distances and Apparent Sizes

Star Party Etiquette

Glossary

Index

INTRODUCTIONWhat's Unique about This Book? This book presents a unique approach to learning the night sky, an approach developed through and successfully used in teaching stargazing courses for many years. The entire sky (visible from the Northern Hemisphere) is divided into nine regions. Each region has a story or theme that ties together the constellations within that region. To the new stargazer, partitioning makes the goal of learning the night sky look surprisingly do-able rather than hopelessly impossible. One learns the sky region by region, using the stories and themes to remember the constellations of each region. Purpose and audience Through years of communicating with the general public through my "Stargazer" newspaper column, presentations to children and adults, and teaching stargazing courses, I have acquired a sense of what seems to best speak to most people -- how they best learn, the topics and questions which capture their interests, the level of knowledge most seem to desire as well as the level which goes beyond their interest and understanding. The purpose of this book is to help amateur stargazers enhance their enjoyment of the night sky. They may be "newbies" just bitten by the stargazing bug who want a basic introduction to help them get started. Perhaps they're stargazers with some experience but ready to move to the next level. Or maybe they're advanced stargazers who might find the sky regions, stories and other tidbits presented herein useful as they help others learn the night sky. The writing style, level and format of the book should make it suitable for children as well as adults. No prior knowledge is required or assumed. This book will be most useful to observers in the Northern Hemisphere, and especially those in the U.S. and other mid-northern latitudes. This focus is not intended as a slight to those living in the Southern Hemisphere, nor the beautiful deep southern night sky; rather it merely reflects the extent of this Texas author's experiences and expertise. The information presented is, to the best of my knowledge, sound to the limits of our present-day understandings. However, it is not intended as an astronomy text or a source of in-depth or technical information. There are many excellent resources available for those purposes. Clear skies,

Paul Derrick

Stargazer's Life List

Published in 2004 / ISBN 0-9744875-1-1

Stargazer's Life List, a 270-page, 8½" x 11" spiral-bound book, offers stargazers at all levels a life check list of objects down to the 10th magnitude. Objects are grouped by magnitude providing an objective means for determining one's level of stargazing achievement. |

|

Life Lists

Magnitude Life Lists

Location

Suggestions for Using the Lists

About the Objects and Their Listings

Other Sections of the Book

Abbreviations

Lifer Challenge Lists

1st Magnitude Life List

2nd Magnitude Life List

3rd Magnitude Life List

4th Magnitude Life List

5th Magnitude Life List

6th Magnitude Life List

7th Magnitude Life List

8th Magnitude Life List

9th Magnitude Life List

10th Magnitude Life List

Lifers Beyond the Challenge Lists

Solar System Lists

Brightest Constellations, Stars and Deep-Sky Objects

Constellations

Stars

Open Clusters

Bright Nebulae

Planetary Nebulae

Globular Clusters

Galaxies

Master Index of Objects

Life Lists

Following in the tradition of her grandfather, Texas naturalist Roy Bedichek, my wife, Jane, is a birder. Having accompanied her on many birding expeditions, I often witnessed her joy and satisfaction at sighting a "lifer" – a bird she had never previously seen. Like most serious birders, she keeps a "life list" of all the types of birds she has seen, and she even keeps a running total of the number of birds on her life list.

After several years of birding with Jane, it occurred to me that I, as a stargazer, didn’t have a comparable list of my cosmic conquests. Like most stargazers, I had pages of observing notes, and I’d completed several lists for pins and certificates. But nowhere did I have a composite list of all the objects I’d seen, nor did I even know how many I’d seen. I was envious of Jane and her fellow birders.

So I looked through my library of amateur astronomy books and other resources thinking surely someone must have published a life list for stargazers. But the search turned up very little. I found several "favorites" lists of different individual’s favorite objects, but these were, of course, quite limited. The only attempt at a life list I found was in the back of Leslie Peltier’s The Binocular Stargazer (Kalmbach Publishing, 1995), and while it was similar to what I was looking for, it wasn’t sufficiently comprehensive to satisfy my needs. In keeping with the focus of the book, his list was limited primarily to binocular objects, and the objects selected for inclusion were still rather arbitrary.

Therefore I set about to compile a stargazer life check list that was comprehensive down to the 10th magnitude – what I can ordinarily see with my (at best) average eyes peering through my 8" Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope. The result is the following listing of over 1,200 objects (and phenomena) – solar system, constellations, asterisms and superpatterns, stars, open clusters, bright nebulae, globular clusters, planetary nebulae, galaxies and a few "others."

Magnitude Life Lists

I decided to add another dimension to the life list concept, one that even birders don’t have. In the lists that follow, objects are grouped according to magnitude. All objects brighter than magnitude 1.5 are included in the "1st Magnitude Stargazer Life List," all at least 1.5 but less than 2.5 magnitude are in the "2nd Magnitude List," and so on down to the "10th Magnitude List." And there are two additional lists: "Lifers Beyond the Challenge Lists." and "Solar System."

Grouping objects in this manner provides an objective means for determining one’s level of stargazing achievement, beyond simply the total number of objects seen. A new stargazer, after observing all the objects on the 1st Magnitude List, can consider himself or herself a 1st Magnitude Stargazer. Then she or he can set about to achieve the 2nd Magnitude Stargazer level, and so forth. Those reaching the 8th, 9th and 10th Magnitude Stargazer levels would be veterans worthy of considerable admiration.

Location

Much to the chagrin of most of us stargazers, not all objects are available for observation from our viewing latitudes. (Wouldn’t we in the U.S. love to see some of those Southern Hemisphere beauties like the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, 47 Tucanae and the Eta Carina Nebula?) Therefore, each object is additionally classified as North, Mid or South.

North objects are situated beyond (north of) declination 40° North, Mid objects are between 40° North and 40° South, and South objects are beyond (south of) 40° South. For stargazers in midnorthern latitudes (i.e., most of the U.S.), objects listed under South will never rise above the horizon, or will not rise far enough for easy viewing. The opposite, of course, holds for southern stargazers. Mid objects can be seen from virtually any inhabited place on Earth.

In establishing one’s stargazer level, it seems reasonable that northerners not be required to observe South objects, and southerners not be required to observe North objects. (Those of us living and observing in the southern states are fortunate to be able to see further into the Southern Celestial Hemisphere, which undoubtedly explains part of the popularity of the Texas Star Party held near latitude 30° N.)

Suggestions for Using the Lists

It is intended that this Stargazer's Life List will be used in whatever manner best suits each individual. Since keeping such a list and record is primarily for one’s own satisfaction and personal fulfillment, it is entirely up to each person to deal with related issues, such as establishing the criteria for what is regarded as an observation. The following are offered only as suggestions for your consideration.

Most objects are preceded by "N B T" where N = a naked eye observation, B = a binocular observation, and T = a telescopic observation. The appropriate letter(s) can be circled to record your observation. (Some naked-eye objects, such as constellations, simply have a space for checking them off.) The additional space is provided for whatever notes, if any, you wish to add, such as the date, time and location of your observation, instrument(s) used, and the power(s) at which the observation was made.

Here are some issues you will need to resolve for yourself: Can you count an observation if you used your telescope’s GoTo capabilities to find it? Can you count it if you see it in another person’s scope after they have found it? Do you have to see it in all the ways it can be seen – N, B and/or T – to count it? For what it’s worth, here’s how I resolve these issues for myself.

My ancient scope doesn’t even have GoTo capabilities, but even if it did, I still like the challenge of finding objects on my own and would derive more satisfaction from being able to check off a new lifer if I found it myself. However, if I were unable to find an object without GoTo, I would still count it as an observation and simply record the use of GoTo in my notes. Likewise, when I have observed a new object in another’s scope, I counted it but gave appropriate credit in my notes.

Many objects can be seen in more than one way, and I like to see them in all the ways I can, as far as it is practical and meaningful. For example, it’s satisfying viewing Omega Centauri with naked eyes, through binoculars, and telescopically – each view providing it’s own type of satisfaction. However, I count an object as an observation once I have seen it by any means.

This Life List is intended to supplement, not replace, the observing log or journal many stargazers like to keep. Indeed, it is from log or journal entries that one can record observations on these lists. And it certainly is not meant to replace any of the other observing programs, such as those sponsored by the Astronomical League.

One final user suggestion: for quickly moving from one section to another, I have added tabs to my personal copy. You might wish to do the same. Computer labels cut in half, then folded in half work great.

About the Objects and Their Listings

In determining each object’s magnitude for selection and classification, I primarily used the following data sources:

- Sky Catalogue 2000.0, Vol. 2: Double Stars, Variable Stars and Nonstellar Objects (Alan Hirshfeld and Roger W. Sinnott, Sky Publishing Corp., 1985)

- Sky Atlas 2000.0 Companion [2nd edition] (Robert A.Strong and Roger W. Sinnott, Sky Publishing Corp., 2000)

- The Deep Sky Field Guide to Uranometria 2000.0 (Murray Cragin, James Lucyk and Barry Rappaport, Willmann-Bell, Inc, 1993)

- The Night Sky Observer's Guide, Vols 1 & 2 (George Robert Kepple and Glen W. Sanner, Willmann-Bell, Inc, 1998)

To the best of my knowledge, the list contains the following:

- all major solar system objects (and phenomenon) (151)

- all constellations (88)

- all major superpatterns and asterisms (17)

- all 1st-magnitude stars (21)

- selected multiple, variable and other stars (181)

- all NGC and Messier open clusters brighter than magnitude 10.5, selected others (387)

- all globular clusters brighter than magnitude 10.5 (103)

- all planetary nebulae brighter than magnitude 10.5 (32)

- all bright nebulae brighter than magnitude 10.5 (29)

- all galaxies brighter than magnitude 10.5 (216)

- a handful of other objects that do not easily fit within another category.

The lists include all objects in the Messier and Caldwell catalogs as well as all objects in the Astronomical League's more popular observing programs.

A word regarding magnitudes: as most stargazers know published magnitudes of nonstellar objects can be quite misleading. An object’s magnitude is determined by measuring the total amount of light radiating from it and treating it as if all the light was coming from a single point. The practical effect of this can be considerable in terms of how easy or difficult it might be to see a given object. The larger the object, the more its total light is spread over a larger area, making its magnitude value more misleading.

This especially affects nebulae, star clusters and galaxies. Consider, for example, these four 6th-magnitude objects: M33 (Triangulum Galaxy), M8 (Lagoon Nebula), M13 (Hercules Globular Cluster) and any 6th-magnitude star. All give out about the same amount of light, but their sizes vary considerably. A 6th-magnitude star can be seen more easily than M8 or M13, yet both of these are much easier to see than the larger M33. (Thus M8 and M13 are far more likely than M33 to be showcased at public star parties.)

As for the lists, there may be occasions where you wish to quibble with the magnitude classification of a particular object. Since this is for your own personal use, I would urge you to feel free to modify it as you see fit. There are blank lines at the end of each Magnitude list you may use for moving objects, adding any objects that have been omitted, or for any other notes you wish to make. (If you have suggestions for additions, corrections or changes for subsequent printings, please send them to the author. They will be welcomed and appreciated.)

Other Sections of This Book

The second major section, Brightest Constellations, Stars and Deep-Sky Objects, contains distribution tables of objects to 10th magnitude and summary lists of the brightest constellations, stars and deep-sky objects by type and magnitude. The final section is the Master Index of Objects for easily and quickly locating objects.