Copyright by Paul Derrick. Permission is granted for free electronic distribution as long as this paragraph is included. For permission to publish in any other form, please contact the author at paulderrickwaco@aol.com.

Dec. 23, 2011: January 2012

Dec. 09, 2011: Tycho Brahe, an Unlikely Revolutionary

Nov. 25, 2011: December 2011

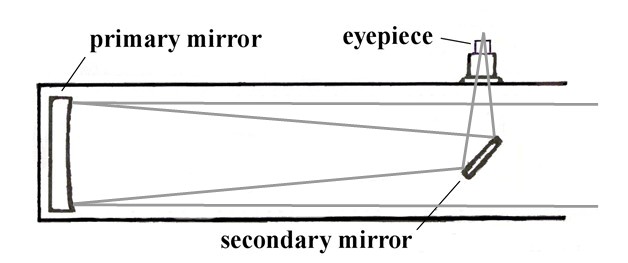

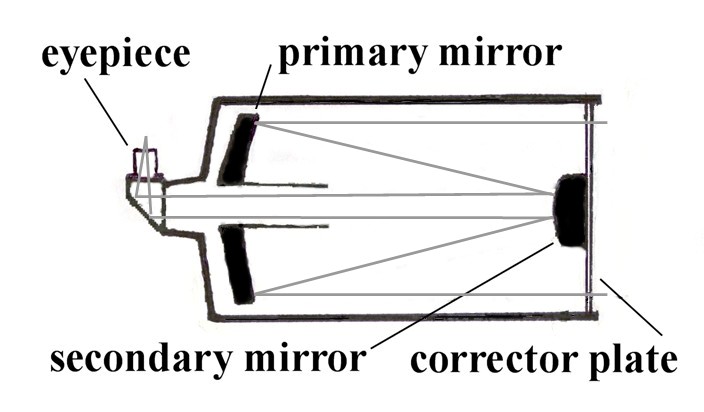

Nov. 11, 2011: Buying a Telescope for the Holidays?

Oct. 28, 2011: November 2011

Oct. 14, 2011: Mystery Sighting

Sep. 23, 2011: October 2011

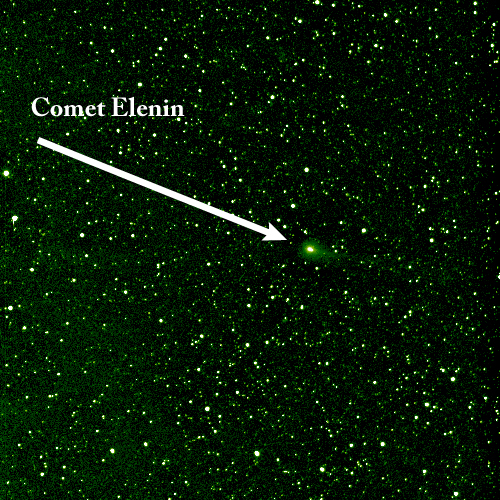

Sep. 09, 2011: Comet Elenin and Other Fables

Aug. 26, 2011: September 2011

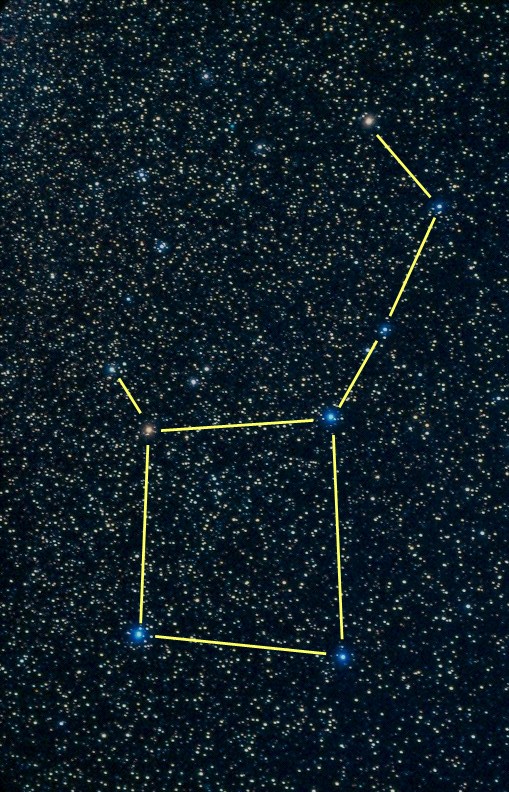

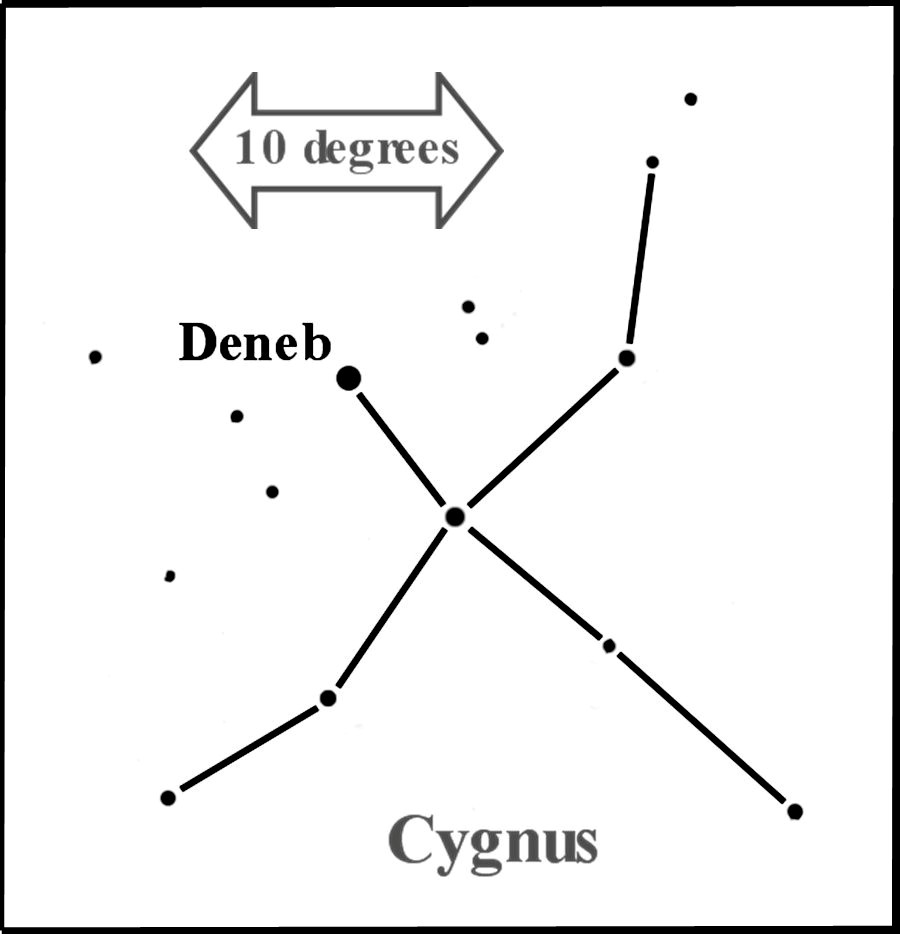

Aug. 12, 2011: Constellations

July 29, 2011: August 2011

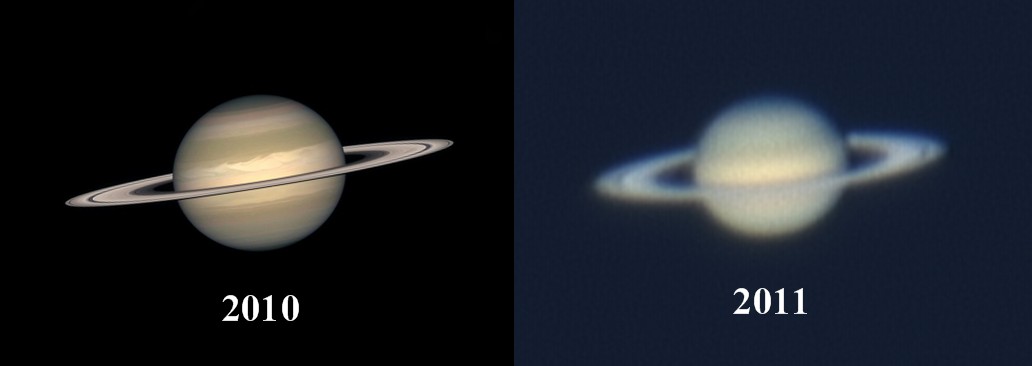

July 08, 2011: Seeing Is Believing...or Is It?

June 24, 2011: July 2011

June 10, 2011: Summer Solstice - the Sun Goes North for the Summer

May 28, 2011: June 2011

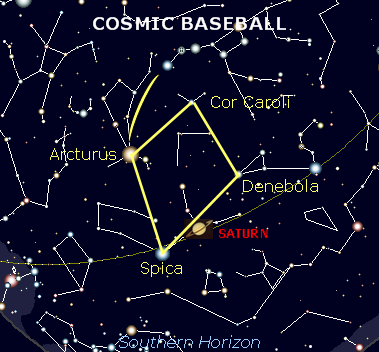

May 13, 2011: Cosmic Baseball

Apr. 22, 2011: May 2011

Apr. 08, 2011: Maria Mitchell - Trail-blazer

Mar. 25, 2011: April 2011

Mar. 11, 2011: Getting to Know Our Solar System: Moon

Feb. 25, 2011: March 2011

Feb. 11, 2011: Giordano Bruno: Martyr or Fool?

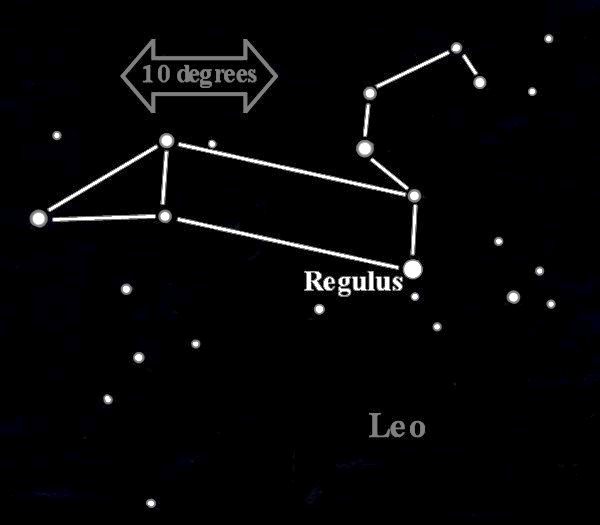

Jan. 22, 2011: Angular Distances

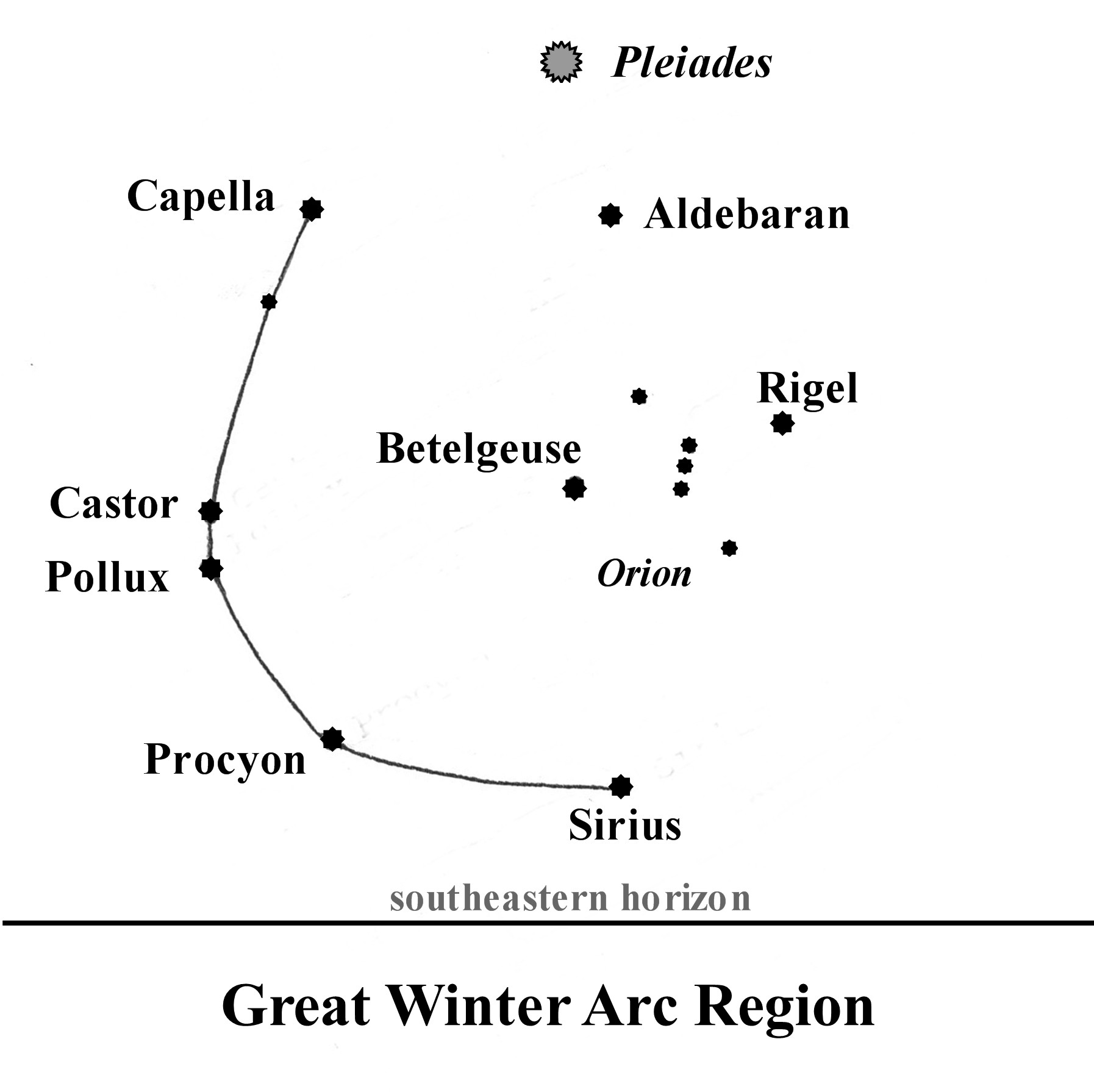

Jan. 08, 2011: The Great Winter Arc

|

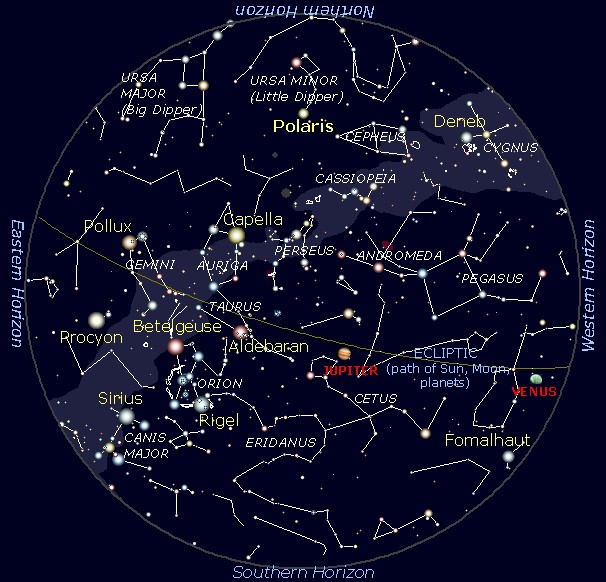

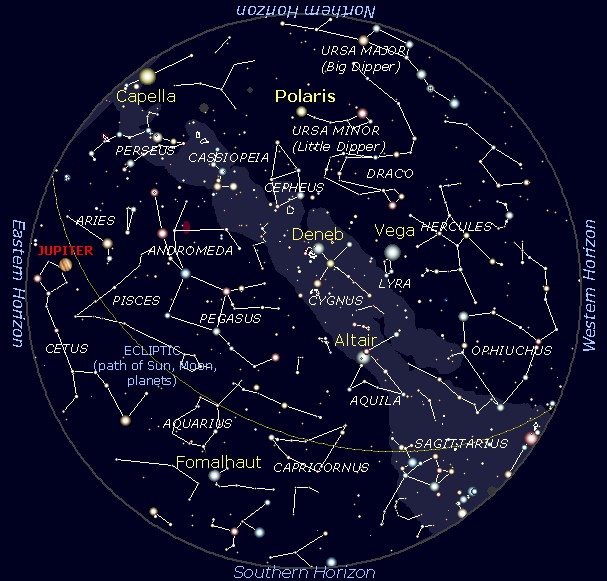

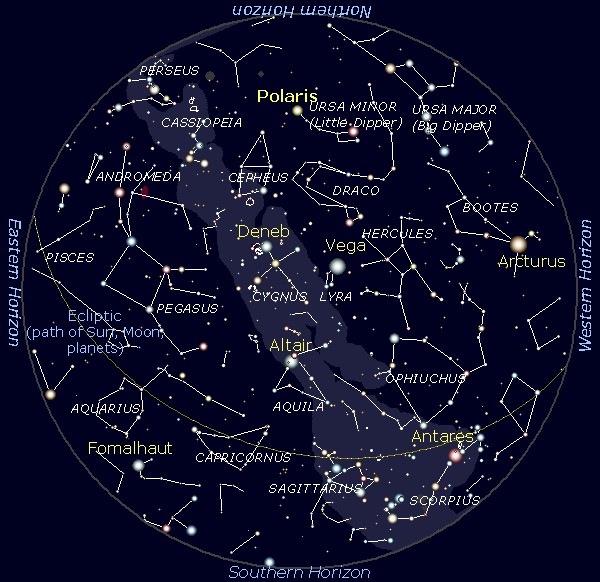

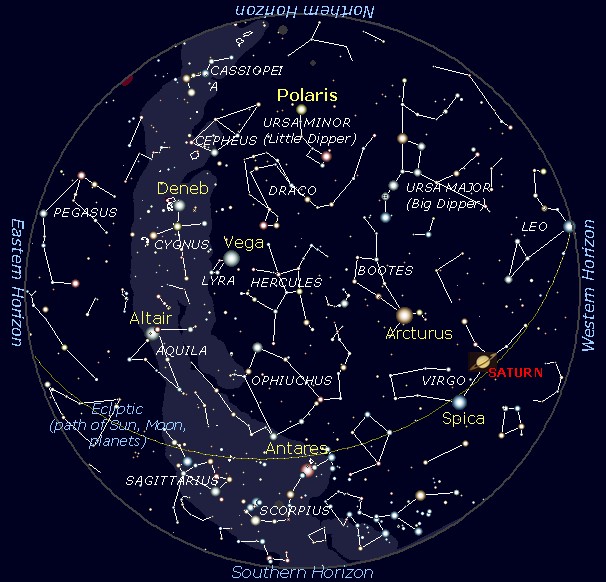

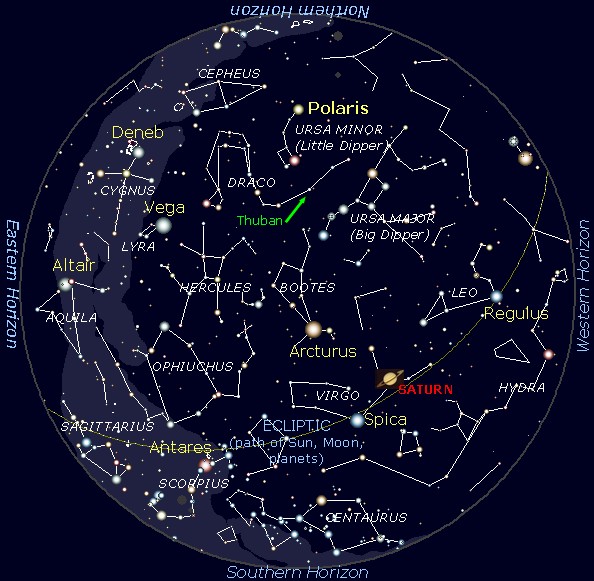

This chart shows the night sky as appears at 9 p.m. early in the month, 8 p.m. at mid month, and 7 p.m. late in the month from latitude 30º N. Hold the chart so the direction you are facing is at the bottom. For example, if you are facing north, turn the chart around so "Northern Horizon" is at the bottom as you hold it out in front of you. The stars on the lower part of the chart are those you will be facing in the sky. The stars at the chart's center represents the part of the sky straight overhead. [Sky chart generated using Cartes du Ciel freeware.] / To keep your eyes adjusted to the darkness as you look a the night sky, use a red-light flashlight to view the chart. You can make your own by putting red cellophane over the light or by coloring the lens of the flashlight with a red marker pen.

|

|

|

|

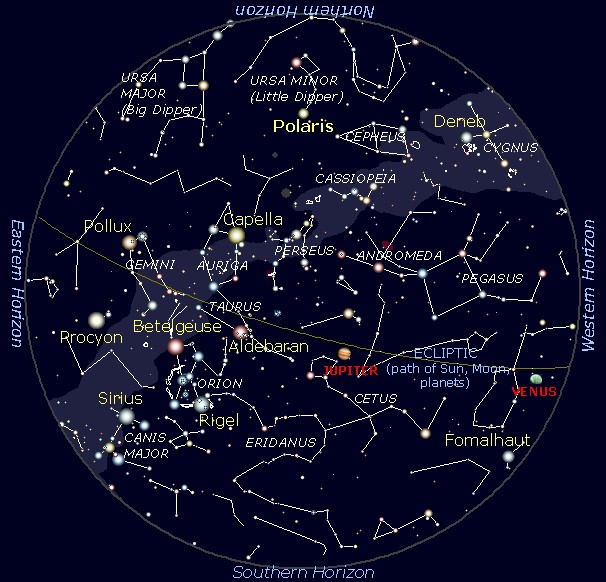

This chart shows the night sky as appears on the 1st at 9 p.m., on the 15th at 8 p.m., and on the 31th at 7 p.m. from latitude 30º N. Hold the chart so the direction you are facing is at the bottom. For example, if you are facing north, turn the chart around so "Northern Horizon" is at the bottom as you hold it out in front of you. The stars on the lower part of the chart are those you will be facing in the sky. The stars at the chart's center represents the part of the sky straight overhead. [Sky chart generated using Cartes du Ciel freeware.] / To keep your eyes adjusted to the darkness as you look a the night sky, use a red-light flashlight to view the chart. You can make your own by putting red cellophane over the light or by coloring the lens of the flashlight with a red marker pen.

|

|

|

|

|

This chart shows the night sky as appears on the 1st at 9 p.m., on the 15th at 8 p.m., and on the 30th at 7 p.m. from latitude 30º N. Hold the chart so the direction you are facing is at the bottom. For example, if you are facing north, turn the chart around so "Northern Horizon" is at the bottom as you hold it out in front of you. The stars on the lower part of the chart are those you will be facing in the sky. The stars at the chart's center represents the part of the sky straight overhead. [Sky chart generated using Cartes du Ciel freeware.] / To keep your eyes adjusted to the darkness as you look a the night sky, use a red-light flashlight to view the chart. You can make your own by putting red cellophane over the light or by coloring the lens of the flashlight with a red marker pen.

|

|

|

This chart shows the night sky as appears on the 1st at 10 p.m., on the 15th at 9 p.m., and on the 31th at 8 p.m. from latitude 30º N. Hold the chart so the direction you are facing is at the bottom. For example, if you are facing north, turn the chart around so "Northern Horizon" is at the bottom as you hold it out in front of you. The stars on the lower part of the chart are those you will be facing in the sky. The stars at the chart's center represents the part of the sky straight overhead. [Sky chart generated using Cartes du Ciel freeware.] / To keep your eyes adjusted to the darkness as you look a the night sky, use a red-light flashlight to view the chart. You can make your own by putting red cellophane over the light or by coloring the lens of the flashlight with a red marker pen.

|

|

|

|

|

|

This chart shows the night sky as appears on the 1st at 10:30 p.m., on the 15th at 9:30 p.m., and on the 30th at 8:30 p.m. from latitude 30º N. Hold the chart so the direction you are facing is at the bottom. For example, if you are facing north, turn the chart around so "Northern Horizon" is at the bottom as you hold it out in front of you. The stars on the lower part of the chart are those you will be facing in the sky. The stars at the chart's center represents the part of the sky straight overhead. [Sky chart generated using Cartes du Ciel freeware.] / To keep your eyes adjusted to the darkness as you look a the night sky, use a red-light flashlight to view the chart. You can make your own by putting red cellophane over the light or by coloring the lens of the flashlight with a red marker pen.

|

|

|

|

|

|

This chart shows the night sky as appears on the 1st at 11 p.m., on the 15th at 10 p.m., and on the 31th at 9 p.m. from latitude 30º N. Hold the chart so the direction you are facing is at the bottom. For example, if you are facing north, turn the chart around so "Northern Horizon" is at the bottom as you hold it out in front of you. The stars on the lower part of the chart are those you will be facing in the sky. The stars at the chart's center represents the part of the sky straight overhead. [Sky chart generated using Cartes du Ciel freeware.] / To keep your eyes adjusted to the darkness as you look a the night sky, use a red-light flashlight to view the chart. You can make your own by putting red cellophane over the light or by coloring the lens of the flashlight with a red marker pen.

|

|

|

|

|

This chart shows the night sky as appears July 1 at 11:30 p.m., July 15 at 10:30 p.m., and July 31 at 9:30 p.m. from latitude 30º N. Hold the chart so the direction you are facing is at the bottom. For example, if you are facing north, turn the chart around so "Northern Horizon" is at the bottom as you hold it out in front of you. The stars on the lower part of the chart are those you will be facing in the sky. The stars at the chart's center represents the part of the sky straight overhead. [Sky chart generated using Cartes du Ciel freeware.] / To keep your eyes adjusted to the darkness as you look a the night sky, use a red-light flashlight to view the chart. You can make your own by putting red cellophane over the light or by coloring the lens of the flashlight with a red marker pen.

|

|

|

|

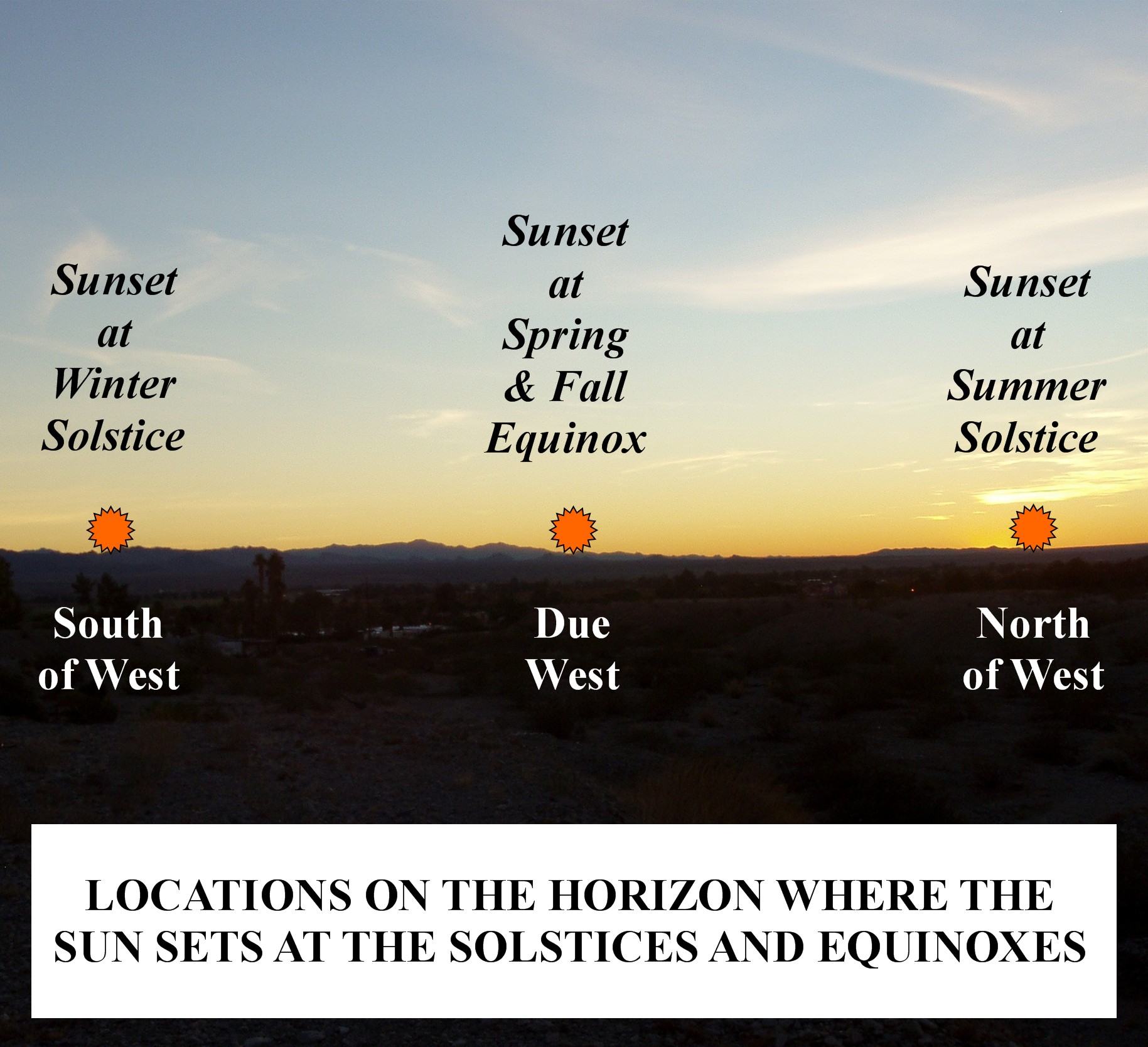

How far north and south of due west the Sun sets (and rises in the east) at the solstice varies with latitude (expressed as degrees above the equator, or below the equator in the Southern Hemisphere). At the equator (latitude 0°), the Sun rises and sets 23½ degrees from due east and west at the solstices, owing to the Earth's 23½-degree tilt on its axis. The further from the equator, the greater the differences become. (For example, here in Waco, TX, at latitude 31.5° N, the solstice Sun sets 28 degrees north of due west, and in Fargo, ND, nearly 37 degrees north of west.) Similarly, the lengths of days and nights throughout the year also vary by latitude. At the equator, days and nights are each 12 hours in length throughout the year, including at the solstices. But this changes as latitude increases. At summer solstice, the year's longest day in Guatemala (15° N) lasts 13 hours while in Waco we have over 14 hours of summer daylight. In Denver (40° N) the day lasts 15 hours, and in southern Canada (50° N) there is over 16 hours of daylight – not leaving much time for stargazing. Alaskans (60° N and beyond) have to do some of their summer sleeping absent darkness as the day lasts some 19 hours and more. And in the Arctic region – in “the land of the midnight Sun” – the Sun doesn't even set in the heart of summer. Having never been there, I can only imagine that would take some getting used to, as would the heart of winter when the Sun never rises. All of this also applies in the Southern Hemisphere, only the dates differ – summer begins in December, fall in March, winter in June, and spring in September. Now that would really take some getting used – like, we'd have to quit dreaming of white Christmases.

|

This chart shows the night sky as appears June 1 at 11:30 p.m., June 15 at 10:30 p.m., and June 30 at 9:30 p.m. from latitude 30º N. Hold the chart so the direction you are facing is at the bottom. For example, if you are facing north, turn the chart around so "Northern Horizon" is at the bottom as you hold it out in front of you. The stars on the lower part of the chart are those you will be facing in the sky. The stars at the chart's center represents the part of the sky straight overhead. [Sky chart generated using Cartes du Ciel freeware.] / To keep your eyes adjusted to the darkness as you look a the night sky, use a red-light flashlight to view the chart. You can make your own by putting red cellophane over the light or by coloring the lens of the flashlight with a red marker pen.

|

|

|

|

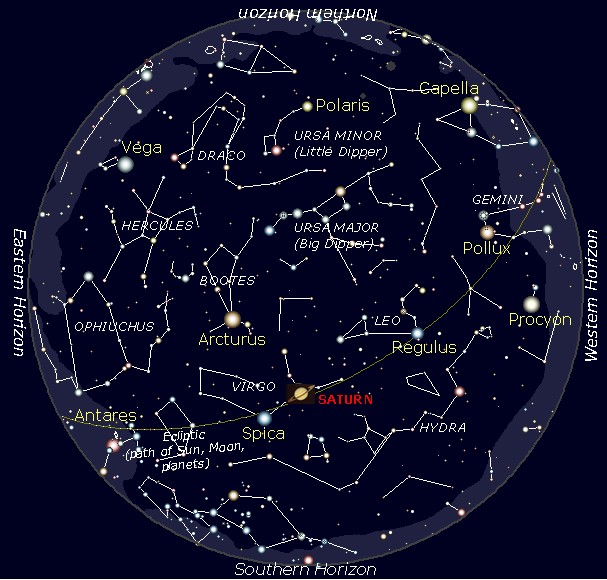

This chart shows the night sky as appears May 1 at 11:30 p.m., May 15 at 10:30 p.m., and May 31 at 9:30 p.m. from latitude 30º N. Hold the chart so the direction you are facing is at the bottom. For example, if you are facing north, turn the chart around so "Northern Horizon" is at the bottom as you hold it out in front of you. The stars on the lower part of the chart are those you will be facing in the sky. The stars at the chart's center represents the part of the sky straight overhead. [Sky chart generated using Cartes du Ciel freeware.]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

, Campo de' Fiori, Rome- pub dom.jpg)

|

|

|