Copyright by Paul Derrick. Permission is granted for free electronic distribution as long as this paragraph is included. For permission to publish in any other form, please contact the author at paulderrickwaco@aol.com.

NOTE: With the Aug. 24, 2012, column, my Stargazer column is being retired. Having just turned 72 years of age, and after 22 1/2 years of writing 587 columns, I've enjoyed about all I have the energy to handle. I truly hope you've enjoyed Stargazer and will continue to visit this website for its other features. And note, with the exception of 1993-1997, previous Stargazer columns can be seen in the archives.

Regards, Paul

Aug. 24, 2012: September 2012

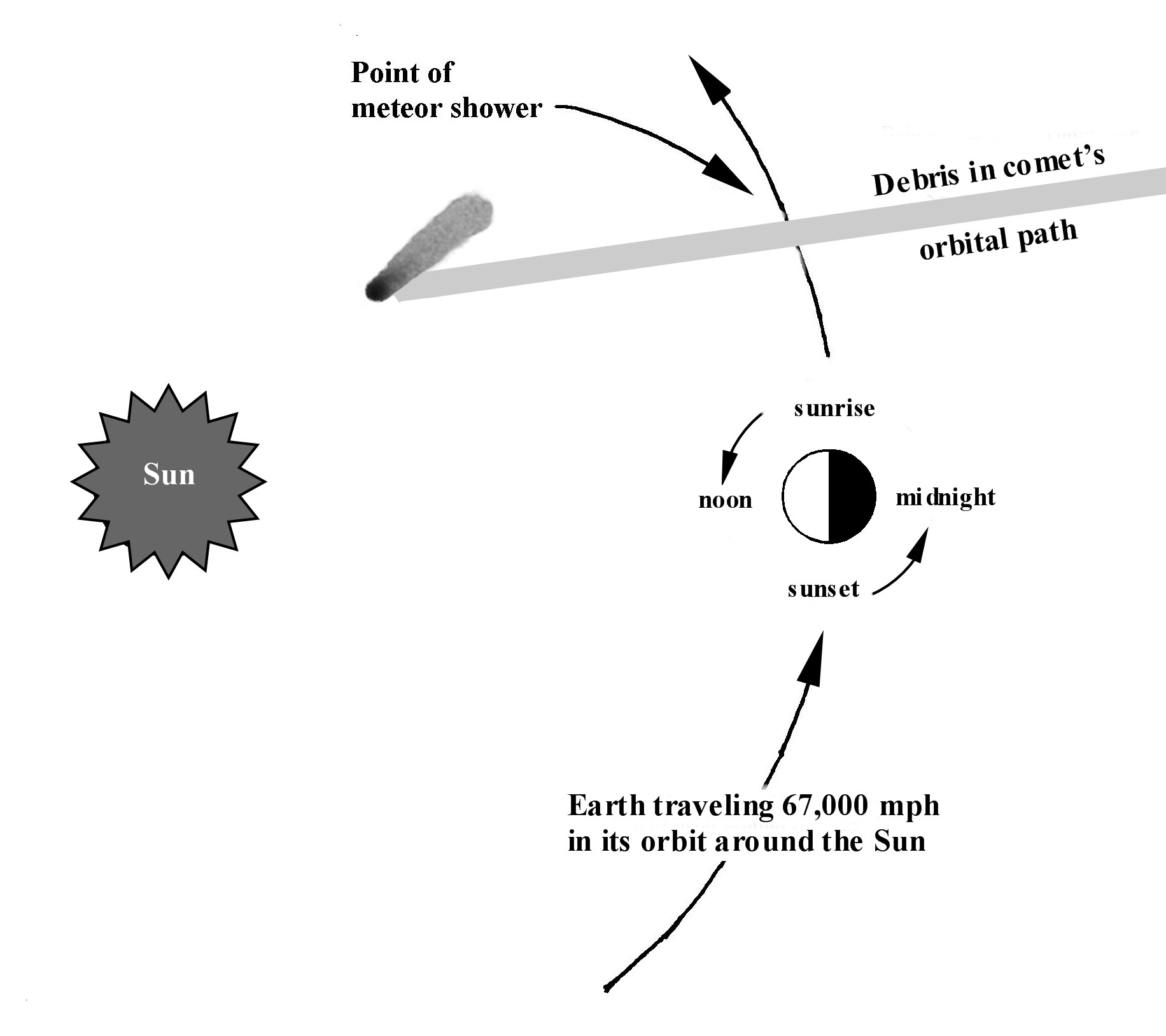

Aug. 10, 2012: Perseid Meteor Shower

July 27, 2012: August 2012

July 13, 2012: Star or Planet -- How Can You Tell?

June 22, 2012: July 2012

June 08, 2012: Stargazing in the Summer

May 25, 2012: June 2012

May 11, 2012: Transit of Venus

Apr. 27, 2012: May 2012

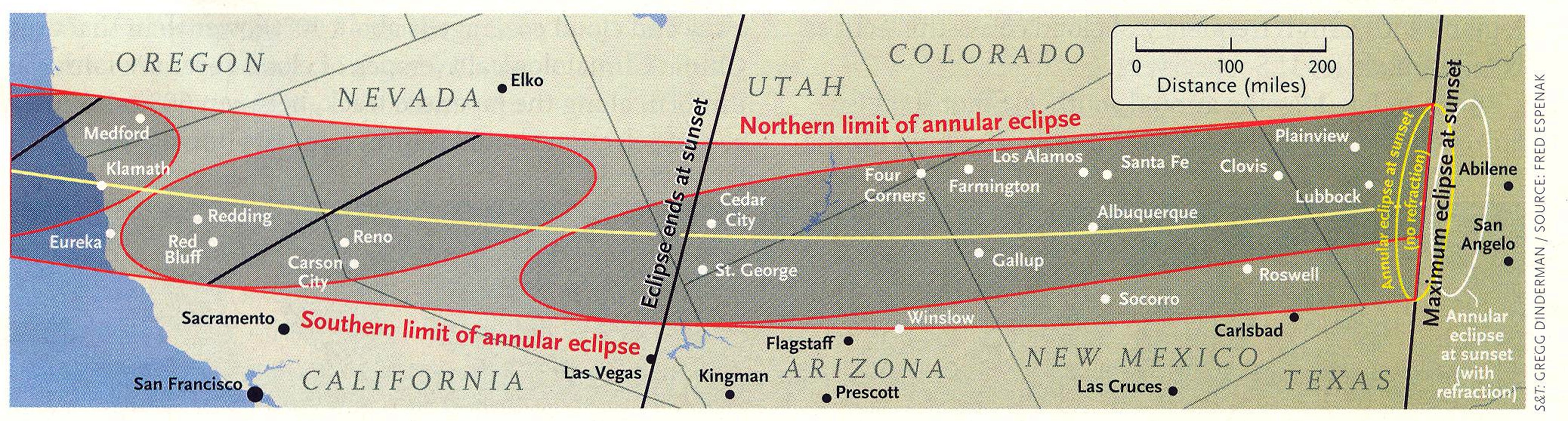

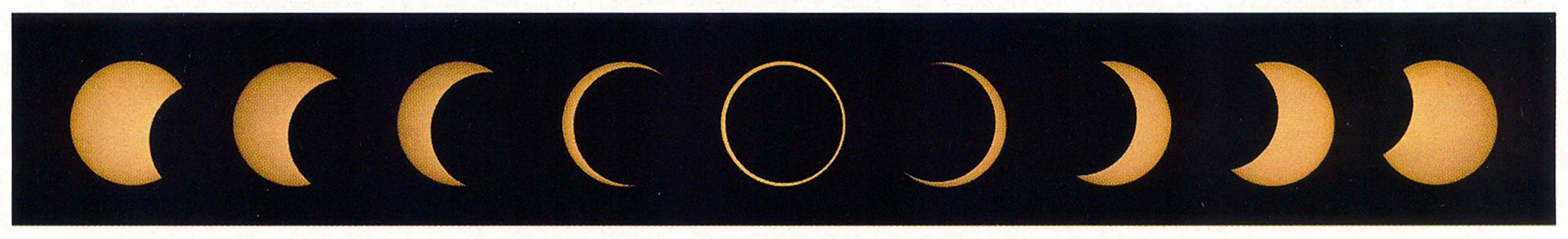

Apr. 13, 2012: Solar Eclipse Coming Our Way

Mar. 23, 2012: April 2012

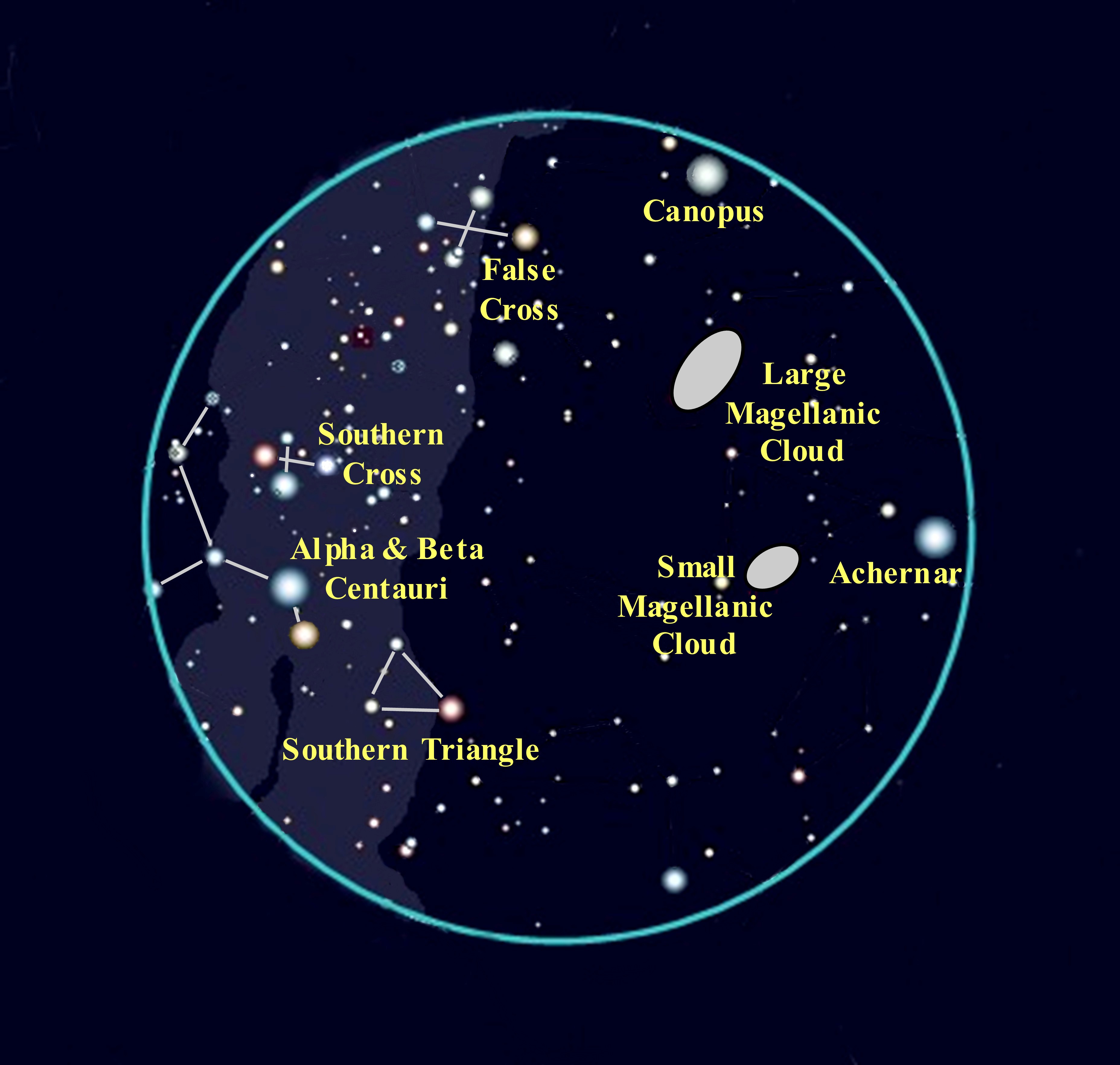

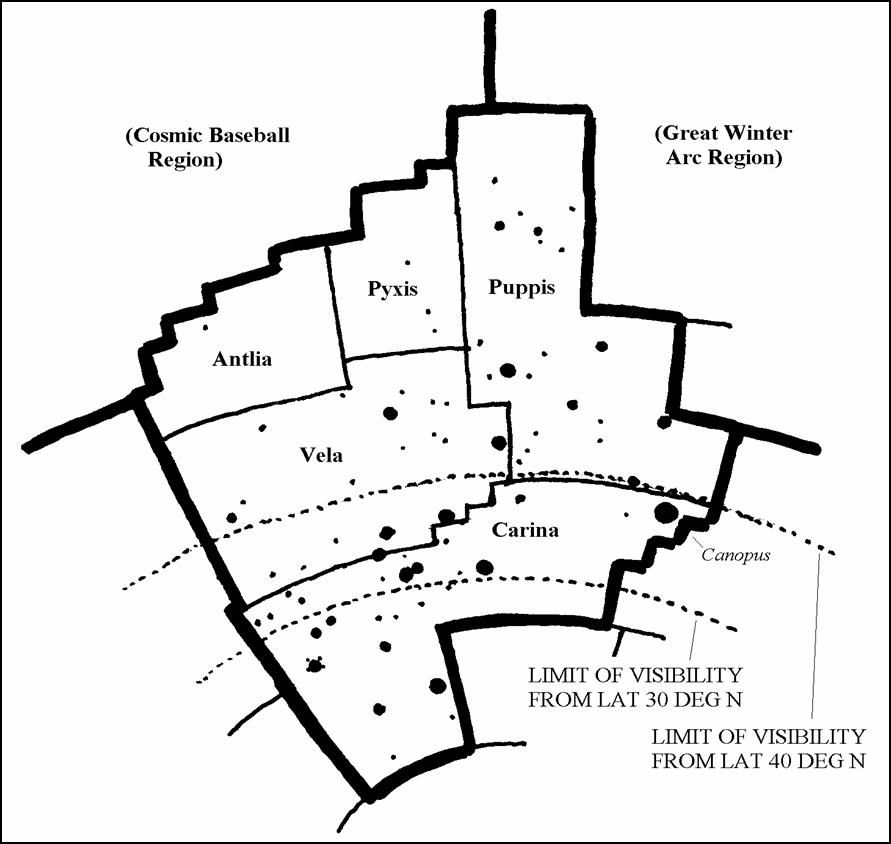

Mar. 09, 2012: More Stargazing Below the Equator

Feb. 24, 2012: March 2012

Feb. 10, 2012: Stargazing Below the Equator

Jan. 27, 2012: February 2012

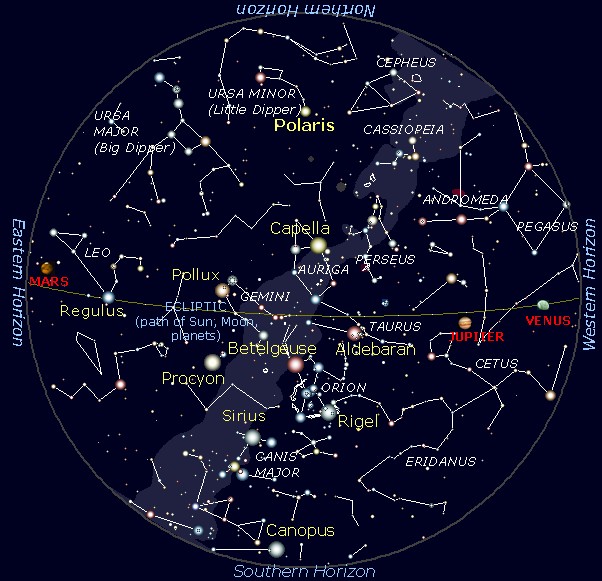

Jan. 13, 2012: 2012 Night Sky Highlights

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

edited.jpg)

|

edited.jpg)

|

|

|

|

edited.jpg)

|

|

|

|

|

|